Please enter the code provided to you by Pallium Canada in order to use this application

Pallium Canada is a national, pan-Canadian not-for-profit organization that aims to improve Palliative Care across Canada through community-building and education of health professionals and carers. It was established in 2001 and since then hundreds of courses have been delivered and thousands of health professionals across different disciplines and professions have been trained.

Every Canadian who requires palliative care will receive it early, effectively and compassionately.

To educate health care professionals and carers about palliative care and to accelerate the integration of palliative care in Canadian communities and healthcare systems.

Visit our website to learn more about Pallium Canada

The origins of palliative care began in the hospice movement. "Hospices" were originally places of rest and care for travelers dating back many centuries. In the 19th century religious orders established hospices in London and Ireland for dying people, often the homeless. It was while working in two such hospices in the 1950's that the founder of modern-day hospice and palliative care, Dame Cicely Saunders, decided to improve the care of terminally ill patients. She had initially trained as a nurse and then as a social worker. She went on to train as a physician to enhance her ability to provide care for these patients. In 1967 she opened St. Christopher's Hospice in London, a hospital (hospice) specifically dedicated to caring for the terminally ill. She also championed and pioneered research and education in the field. She always acknowledged the role that patients and other pioneers across the world had in promoting hospice and palliative care.

In the early 1970's , Dr. Balfour Mount, a Canadian, Montreal-based surgeon and urologist, visited St. Christopher's Hospice and brought the concept to Canada. He coined the term "palliative care" because the term "hospice" had negative connotations in French. In 1973 he opened a palliative care unit in the Royal Victoria Hospital in Montreal. At the same time a similar unit opened in St. Boniface Hospital in Winnipeg. Dr. Mount, like Dame Saunders and other pioneers in the field, has championed the importance of integrating palliative care throughout the healthcare system.

Today Palliative Care is practiced in many different settings and different services, not only in hospices. This includes palliative care units and palliative care specialist teams in the community and hospitals. It recognizes that the responsibility of providing palliative care falls both on specialist palliative care teams as well as all other health professionals , including providers of primary care (such as family physicians and primary care nurses) and professionals working in a number of specialty fields, including internal medicine, cardiology, pulmonology, neurology, nephrology, medical and radiation oncology, geriatrics and care of the elderly, critical care, and emergency care (to mention a few). It recognizes the important role of volunteers, a role that goes back centuries.

In an effort to allay confusion between the terms (and concepts) "hospice" and "palliative care", the term "Hospice Palliative Care" came to be used in the early 2000's in Canada by the Canadian Palliative Care Association (which is now called the Canadian Hospice Palliative Care Association or CHPCA) . Palliative care is therefore practiced in hospices as well as in many other settings where patients with life-threatening and life-limiting illnesses and their families are cared for (home, community, hospitals, palliative care units, retirement homes, long term care or continuing care facilities, etc.).

The term "hospice" has come to mean different things in different countries. In Canada, as in the United Kingdom, it largely refers to a residential facility (often free standing but sometimes within another facility such as a long term care facility) that provides end-of-life care (last days and weeks of life). Hospice programs often also provide volunteer-based day-hospice programs and home visiting programs. Palliative Care Units generally care for patients with complex needs across the illness trajectory (not only at the end of life) and are generally housed in hospitals or complex continuing care facilities. In the United States, "hospice" generally refers to home-based care in the last months of life. There are however also residential hospices for end of life care.

Versus

Mrs. K, a 55 year-old lady, is diagnosed with lung cancer. At the time of diagnosis the cancer is found to have spread locally; there are no distant metastases. Surgery is not an option. Cure is unlikely. She is experiencing pain and anxiety. She undergoes radiotherapy and chemotherapy with the goal of controlling the disease. She believes the treatment was for cure. The treatment leaves her with fatigue, nausea and a depressed mood. No-one addresses these problems.

A few months later her pain worsens and she starts experiencing more shortness of breath. Further tests show the cancer has progressed and there are metastases in the chest and bones. She is devastated. Mrs. K agrees to 2nd line chemotherapy offered by her oncology team. She experiences side effects. She also notices that she is losing a lot of weight. When she complains of this she is referred to a nutritionist. The oncology team tells Mrs. K that when she feels stronger they could consider other chemotherapy. Mrs. K goes home and tries to eat as much as she can to gain weight so that she can receive other chemotherapy treatment. This makes her more nauseous.

She starts experiencing more pain, shortness of breath, weight loss and anxiety and her functional status starts to decline. She is spending more time sitting and resting. She finds it difficult to go to the cancer centre. The oncology team informs her that there is nothing more they can do and refer her for palliative home care. She and her family are very distressed by this. They say that "they did not see this coming." They become even more distressed when the home care team asks her about Advance Care Planning and recommend a Do-Not-Resuscitate status (DNR). These had never been discussed with her previously and she feels like everyone is giving up on her.

Her family physician informs the family that she does not do home visits. They have to find another physician. Unfortunately she develops severe pain and confusion and is taken to the Emergency Department. She is admitted to hospital where the palliative care team are consulted and treatments are started to control her pain and confusion. She dies several days later in hospital in a three-bed ward. The family are upset that they never really got to say goodbye to her and that she spent her last days in hospital.

Mr. G is a 69 year old man with advanced congestive heart failure (CHF) (ejection fraction of 18%) who has been brought to the emergency department with severe shortness of breath (NYHA Class IV), episodes of syncope and severe swelling of his legs. He has an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) and this has fired twice in the last 24 hours. Over the last months he has experienced increasing shortness of breath, edema of the lower legs and weight loss, despite adjustments to his medications. Both he and his family are very distressed.

His CHF was diagnosed about 5 years ago and is related to long-term hypertension. He has visited his cardiologist regularly and has been on medications for several years, including ACE inhibitors, b-blockers and diuretics. He has been hospitalized twice in the last six months because of his heart condition. An implantable cardioverter defibrillator device (ICD) was inserted during the last admission because of cardiac arrhythmias. His and his family's understanding is that this device will keep him alive for many more years.

The on-call cardiologist (who is not his regular cardiologist) is called to see him and the cardiologists asks him and his wife what his goals of care are and whether anyone has spoken to him about advance care planning. The doctor says that it would be important to consider starting palliative care and focus on quality of life at this time, particularly given his failing kidneys and very poor heart function.

Mr. G and his wife are very distressed. He asks the cardiologist "Am I dying?" The cardiologist says "I don't want to lie to you but there is a high risk that it could happen. We could consider admitting you to ICU but if things get worse you will likely need to be put onto life support machines and given the poor condition of your heart, this may not provide you good quality of life."

Before he can decide about his goals of care and DNR status, he loses consciousness and the ICD shocks him twice; this is distressing to his wife and she does not know what to do. His children, who have arrived in the ED, are also not sure what to do. He gets taken to the ICU where he dies several days later on life support machines; during the last days the ICD shocked him several times until the ICU team convinced the family to have it switched off.

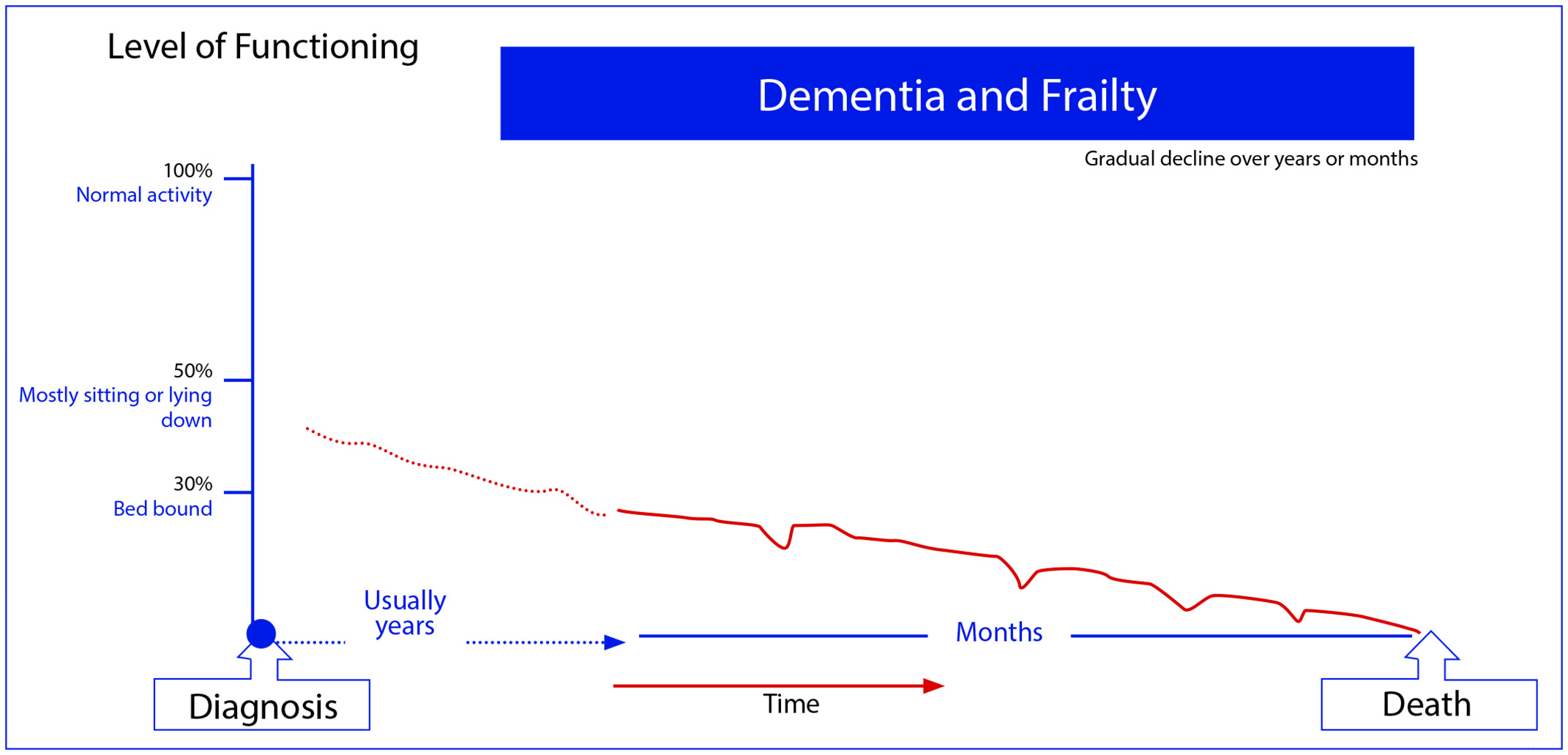

Both Mrs. K and Mr. G experienced a disease that progressed over time. Most of us, like these two patients, will experience an illness trajectory with gradual progression and functional decline (sometimes over weeks or months and sometimes over years) before our deaths. Only 10% of deaths occur suddenly and unexpectedly (e.g. massive stroke, myocardial infarction or accident).

Despite clear signs of disease progression and functional decline, the treatment focus for both patients continued to be cure or control; or at least the patients and families were left with this impression. There were no discussions earlier about prognosis or advance care planning. Realistic goals of care were not discussed until the very end, taking the patients and their families by surprise and thereby increasing their distress and not allowing them any opportunity to prepare for end of life.

There was no attention to symptoms, psychological and social, and spiritual well-being and quality of life, until the terminal phase. They both experienced needless symptoms and suffering for many months before palliative care was finally initiated days before their deaths.

Both died in acute care settings. While acute care settings are appropriate for some persons (particularly when disease progression is unexpected and rapid, resulting in complex complications that require hospitalization for treatment), in many cases such settings can be avoided if advance care planning is done earlier, goals of care are discussed and there is better planning ahead in the context of clear signs of disease progression.

Mr. G experienced painful and uncomfortable ICD shocks even while dying. These could have been avoided if there had been discussions about prognosis and quality of life and quality of dying earlier. Mrs. K ended up being admitted to the Emergency Department and hospital to spend her last days of life.

All of this could have been avoided with earlier introduction of a palliative care approach. Click here to learn why Early is better.

Examples:

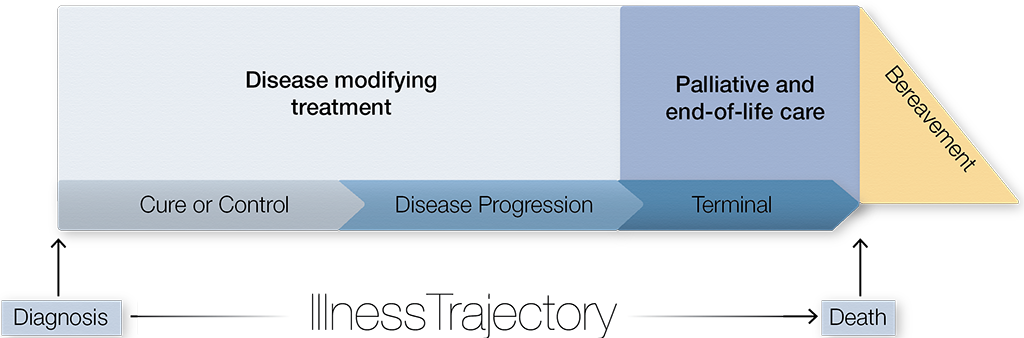

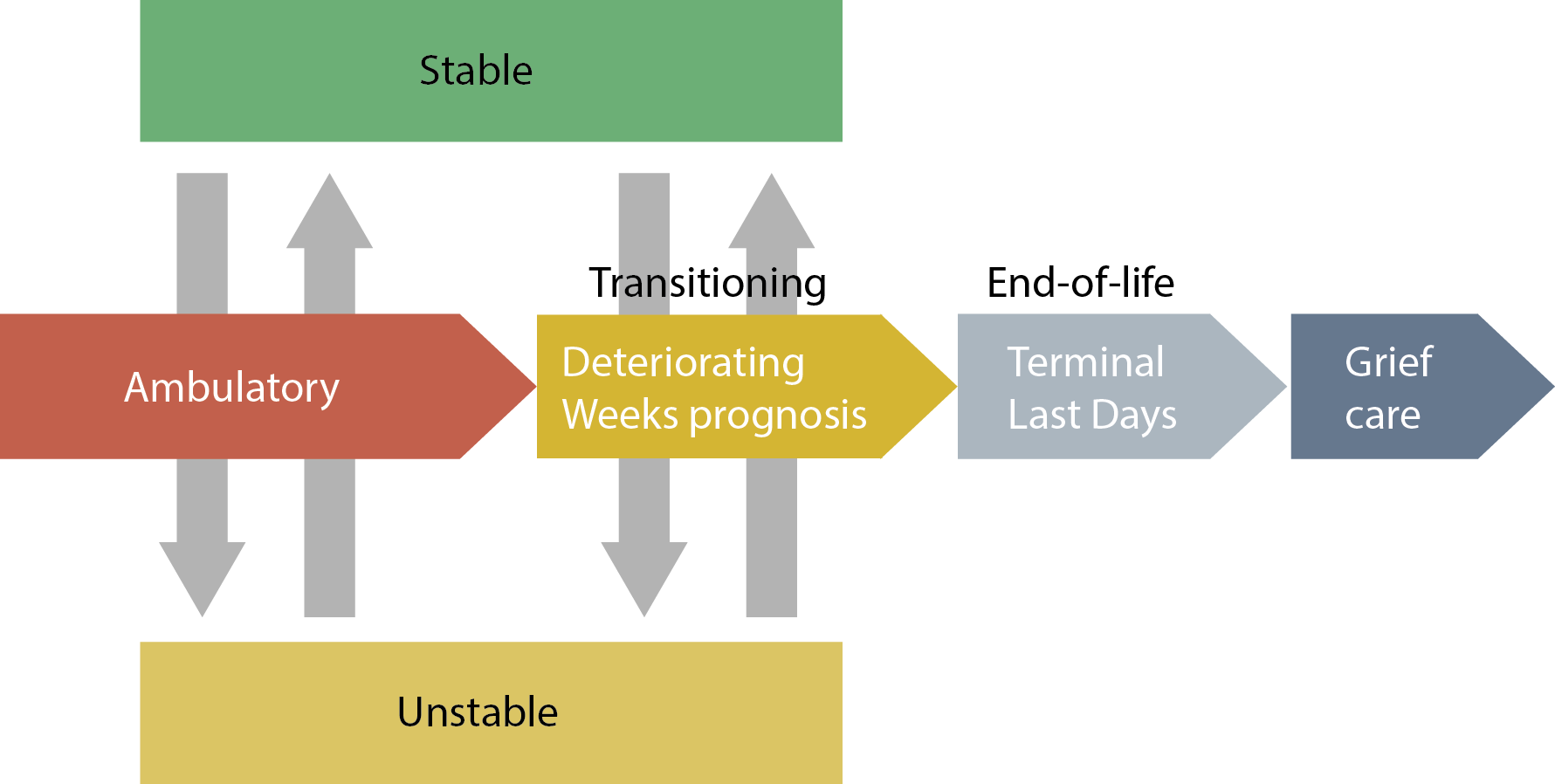

Supportive & Palliative Care begins early in the illness trajectory, alongside treatments to control the disease.

Examples: Treat hypercalcemia, infections, delirium, fractures, GI obstruction, heart failure, etc.

When the illness progresses and the patient enters the terminal phase (end of life), the focus of care turns more towards comfort measures

Bereavement care is often forgotten. This is a key component of palliative and end-of-life care. In fact, it often begins even before the death when the patient and family experience anticipatory grief. It also includes identifying family members at risk for complicated grief reactions after the death.

Mrs. K, a 55 year-old lady, is diagnosed with lung cancer. At the time of diagnosis the cancer is found to have spread locally; there are no distant metastases. Surgery is not an option. She understands that cure is unlikely but that control of her disease for as long as possible is a realistic goal. She undergoes radiotherapy and chemotherapy with the goal of controlling the disease. At the same time her symptoms are assessed by her oncology team and she is found to be experiencing moderate levels of pain and anxiety. A weak opioid is initiated by her oncologist to control her pain and the combination of this and the radiotherapy successfully controls the pain. Her anxiety is explored and supportive counselling is provided by her oncology nurse. She is encouraged to continue seeing her family physician.

A few months later her pain worsens and she starts experiencing more shortness of breath. Further tests show the cancer has progressed and there are metastases in the chest and bones. She is devastated and experiencing significant sadness. Her oncologist refers her to the psychosocial program at the Cancer Centre. She also discusses the various treatment options with Mrs. K. Although 2nd line chemotherapy may be an option, it does not appear to offer significant benefits; neither significant life prolongation nor significant symptom control. They decide that the most appropriate goal of care would be to optimize quality of life. Given that her functional status is still reasonable at this time, this would include treating any complications of the disease that may arise, such as infections or hypercalcemia. Her oncologist also encourages to review her advance care plans and to identify a power of attorney. They also discuss code status and she requests a DNR status. She is also connected with palliative home care and starts seeing her family physician in his clinic.

A few weeks later she presents to her family physician with increased shortness of breath, a productive cough, fever and somnolence. Tests (blood work and a chest x-ray) show that she has a pneumonia and hypercalcemia. Antibiotic treatment is started and she is referred to the day hospital where she is treated with a bisphosphonate infusion to reduce the calcium level. A few days later she is feeling much better and visits her son in another province.

Over the ensuing weeks she spends lots of quality time with her family. Adjustments are made to her pain medications to control her symptoms (pain and dyspnea). Medications that are no longer useful given the goals of care, are discontinued. These include her cholesterol lowering medications and calcium and vitamin D.

Several weeks later she experiences a pain crisis. Initial attempts at treating this at home (including a visit by the specialist palliative care consultation team) are unsuccessful. She is admitted to a local acute palliative care unit where the pain is treated. She is discharged again home 10 days later, where she stays for another 45 days until her death, surrounded by her family. Her family physician provides bereavement care to her husband because he is also the husband's physician. The husband is also connected to a community grief and bereavement program.

Mr. G is a 69 year old man with advanced congestive heart failure (CHF) (ejection fraction of 18%). He is being cared for at home and has been connected with palliative home care for several months. His family physician does occasional home visits. His family physician and home care nurses have access to a specialist palliative care consultation team for advice when needed. Dyspnea has been well controlled with a small dose of morphine. This was already started several months ago when he first started experiencing shortness of breath with mild exertion. He continues to be on his heart medications (diuretics, ACE inhibitor and B-blocker) and these, particularly the diuretics, have recently been adjusted to help control his symptoms (dyspnea and pedal edema). He has a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order in place and his wish is to die at home or a hospice, depending on his needs and the impact on his family (unless his symptom become very severe in which case he wishes to be admitted to a palliative care unit for symptom control at the end of life).

His CHF was diagnosed about 5 years ago. Over the years he has been cared for by both his cardiologist and his family physician (his cardiologist always encouraged him to stay connected to his family physician). With every visit to them, they examined him and adjusted his heart medications to optimize control of his CHF. Periodically they did investigations to guide treatment and understand the extent of the disease. They also regularly assessed his symptoms and periodically explored for psychosocial and spiritual needs. They occasionally touched base on the goals of care; particularly when there were signs of disease progression despite the treatments. They discussed prognosis and realistic goals of care ("if cure is not possible, what is possible?"). Within that framework the focus was on controlling his disease as best as possible while at the same time ensuring optimal quality of life and undertaking advance care planning.

Several months previously, when he was experiencing palpitations and episodes of syncope as a result of dysrhythmias, it was deemed appropriate to insert an implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD). Over the months this had fired once. However, as his functional status declined and he lost a lot of weight and started experiencing shortness of breath at rest (NYHA Class IV), he and his cardiologist and family discussed goals of care and appropriate end-of-life care. They decided to switch off the ICD, recognizing that care would continue but at least he would not experience painful shocks and futile prolongation of life without good quality.

Mr. G dies comfortably, surrounded by his family and with the support of home care services and a family physician.

Both Mrs. K and Mr. G experienced a disease that progressed over time. Most of us, like these two patients, will experience an illness trajectory with gradual progression and functional decline (sometimes over weeks or months and sometimes over years) before our deaths. Only 10% of deaths occur suddenly and unexpectedly (e.g. massive stroke, myocardial infarction or accident).

Initially (at the beginning of the illness trajectories), the main focus was on controlling the diseases (in some cases even curing). However, symptom control and attention to psychological, social and social well-being as well as quality of life were also started. These two goals of care- treatments to modify and control the disease and palliation- are not mutually exclusive and occurred at the same time. Advance care planning was also initiated early and the patients and families were connected to palliative care resources.

Later, as the disease progressed and treatments to control the disease became less effective, the palliative care approach became more prominent. It was a gradual, seamless transition in both cases.

Introducing palliative care early did not increase psychological distress (depression or anxiety) but resulted in better quality of life and better care decisions as well as healthcare resource utilization. A study in 2010 by Temel and colleagues, published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that introducing palliative care early in the illness of patients who had incurable lung cancer at the time of diagnosis resulted in significantly less depression, anxiety and symptoms and improved quality of life when compared to patients who were referred to a palliative care service only at the end of life (last days or weeks)(1). Moreover, patients who received early palliative care (at the same time as radiotherapy and chemotherapy) lived about 3 months longer. More recent studies involving patients with other types of cancer and non-cancer diagnoses have demonstrated similar results, particularly with respect to improved quality of life (2,3).

The model of early integration of a palliative care approach (whether it be provided by the attending physician or a specialist palliative care service) should replace the current "late" model. The "early" model avoids the often abrupt and traumatic transitions of care from curative or control to "palliative" or "hospice" at the EOL. In the earlier phases of a disease, when the main focus of care may be on controlling the disease, palliation can optimize symptom control, quality of life and goal of care discussions. Palliation becomes the main focus as the disease advances and EOL approaches (See the Pallium Doodle "Better early than late". This does not mean that all patients should be referred to specialist palliative care teams, but rather that a palliative care approach should be activated early. This approach can be provided by the physician and team caring for the patient. See "Who provides palliative care")

Palliative care is not the responsibility only of specialist palliative care clinicians and teams. All health professionals who provide any form of care to patients with life threatening and life limiting illnesses should be able to provide basic, primary- or generalist-level palliative care, also known as the "Palliative Care Approach".

A smaller number of patients require specialist-level palliative care services. Palliative care specialists also provide consultation and education support to generalists providing a Palliative Care Approach.

Most palliative and end-of-life (EOL) care can be provided at this primary - or generalist-level. It requires basic palliative & EOL care competencies and the support of palliative care specialist teams.

Patient A: is a patient who has experienced basic palliative care needs throughout his/her illness. These needs were met by a non-palliative care health care professional, such as a family physician, oncologist or internist with good basic skills to provide a palliative care approach. He/she required primary-level palliative care throughout his/her illness. He/she did not require specialist palliative care services.

Patient B: required primary-level palliative care through most of his/her illness but experienced a complex crisis that required the temporary intervention of a specialist palliative care service until his/her situation resolved. Most patients requiring palliative care follow the trajectories of Patients A and B.

Patient C: started off with basic palliative care needs early in the illness trajectory and these were addressed by his/her care team; it did not require a palliative care specialist team. However, at some point in the illness, his/her needs became complex and remained complex until his/her death. This required that a specialist palliative care team take over the responsibility of providing palliative care (at a specialist level).

Patient D: had complex palliative care needs throughout his/her illness, requiring a specialist palliative care team to provide palliative care. These constitute a small number of patients requiring palliative care.

| Patient and Family Needs | Care Level Required |

|---|---|

| Complex palliative and end-of-life (EOL) care needs | Specialist-level Palliative Care Also responsible for leading education, research, quality improvement and health services planning in the field |

| Needs not complex or very difficult. | Palliative Care Approach Generalist-level Provided by health professionals in family medicine, internal medicine, cardiology, ICU, ED, pulmonology, nephrology, geriatrics, neurology, etc. |

Watch on YouTube

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Palliative care is only for the last days and weeks of life | Fact: Palliative care should start early, when a disease is found to be serious and life threatening. Palliative care should start as soon as a disease is deemed to be progressive and incurable. When done earlier, it can be done alongside treatments to control the disease. The palliative approach to care results in better quality of life, reduced depression and anxiety, and in some cases a longer life expectancy. |

| Starting palliative care means I'm dying | Fact: Starting palliative care early means many more months of better quality of life. Many people would benefit from palliative care long before their disease is in the terminal phase. Palliative care focuses on improving quality of life and engaging in important discussions - no matter how long one has to live. |

| Palliative care starts when there is no further active treatment available | Fact: Palliative care is active care. Palliative care is very active care. It requires:

|

| Starting palliative care means giving up | Fact: Starting a palliative care approach means that care continues. Starting palliative care means changing the goals of care. It doesn't mean "giving up" as there is always ongoing and active care to be done! |

| Palliative care means getting doped up with morphine until the end | Fact: The goal of palliative care requires effective and judicious use of medications. Morphine and other opioids are safe and effective medications when used appropriately to treat pain. The goal is to control pain and have a person clear of mind. Becoming increasingly sleepy and fatigued is a normal part of dying. Too often morphine is blamed for this when it's actually innocent. |

Watch on YouTube

| Myth | Reality |

|---|---|

| Palliative care is only for the elderly. | Fact: Palliative care is applicable for ALL ages! Life threatening and life limiting illnesses occur across all age groups. Although more common in older people, younger people also develop progressive incurable illnesses. |

| Palliative care is just for patients with cancer. | Fact: Palliative care is for all life limiting illnesses, cancer OR non-cancer. Palliative care is applicable for many different diseases, not only cancer. This includes advanced heart, lung, kidney and neurological diseases such as dementia and ALS. |

| Palliative care is done only by palliative care specialist teams. | Fact: Palliative care is the responsibility of all health professionals who, in the course of their work, provide care to patients with life threatening and life limiting illnesses. All health professionals who care for someone with a life threatening or life limiting illness should know the essentials of good palliative care. Family Doctors, Nurses, Oncologists, Cardiologists, Pharmacists, Social Workers, Dieticians, Physiotherapists, Occupational Therapists, Ethicists, Spiritual Care Providers, should all have training. We cannot rely only on a small number of palliative care specialists to provide palliative care. |

| Everyone has access to good palliative care. | Fact: Work still needs to be done by health services across the country to fully integrate palliative care and ensure access to palliative care. Only 16 to 30% of Canadians have access to palliative care and most of them only receive palliative services within the last days and weeks of life. |

| People are immortal. | Fact: No one is immortal.Everyone dies someday, and today, sudden death is much less common than it once was. The World Health Organization states that in Canada chronic diseases are projected to account for 89% of all deaths. |

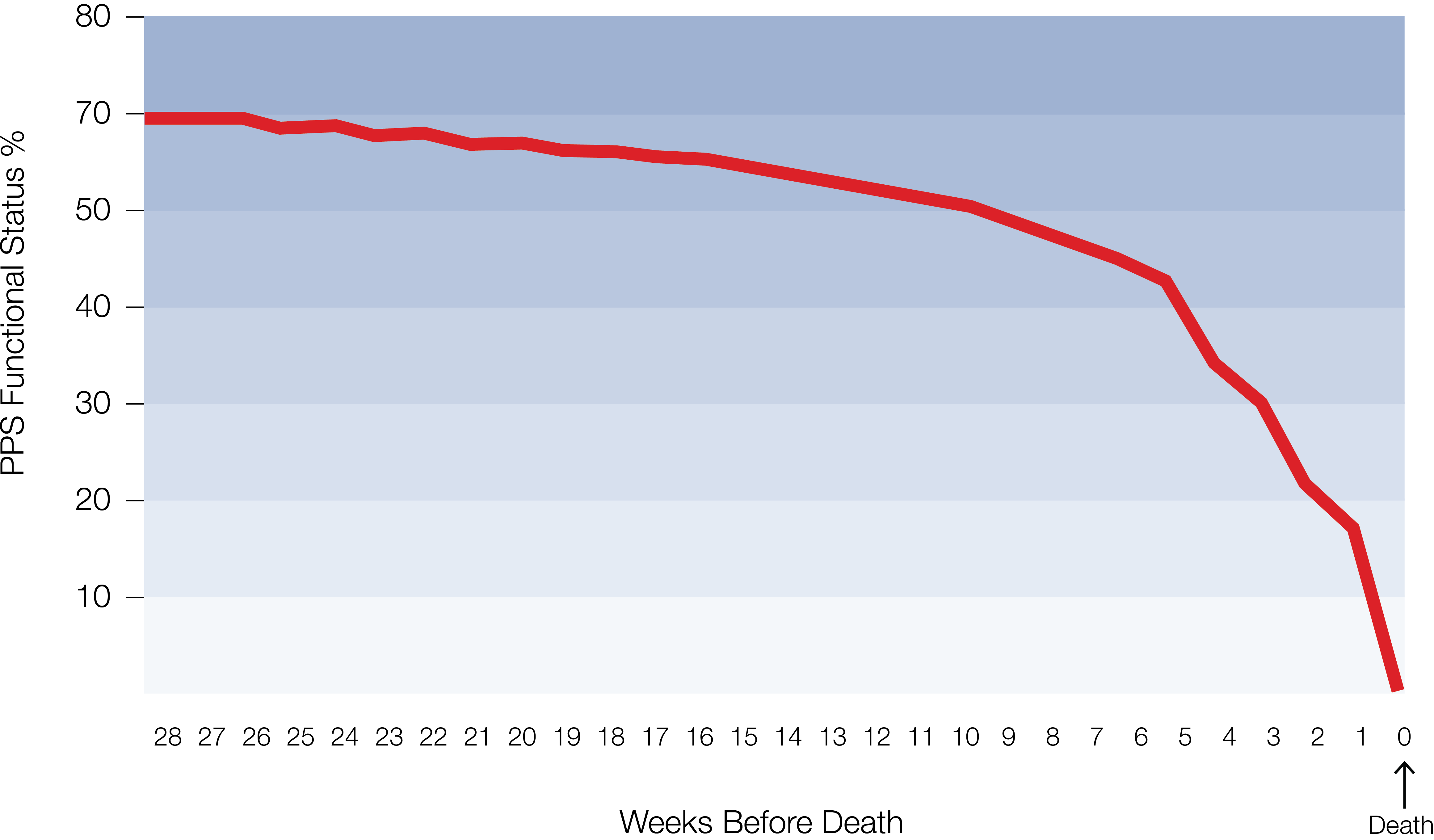

This represents the average curve. A large study by Barbera and Seow et al in Ontario of several thousand cancer patients confirmed this trajectory. However, some cancers are beginning to take on a chronic illness trajectory (see Chronic End-stage heart/lung Illness Trajectory.

Studies show that in advanced lung cancer, for example, life expectancy when a patient has a PPS of 50% is in the order of several weeks to a few months.

For some cancers the terminal phase can be more abrupt, while for others more gradual.

Note that for some patients, e.g. with endstage heart failure, death can be relatively sudden at any time in the illness trajectory.

Codeine is a convenient first line weak opioid. If there is a neuropathic pain component, use tramadol instead of codeine. Codeine is not more constipating than other opioids. If pain still not well controlled despite maximum doses, switch to a strong opioid (M or HM). Maximum doses are: Tramadol (400mg per day) and codeine (about 240mg per day). Manage opioid side effects.

| Opioid | Usual Starting Dose | Frail Persons, very elderly and/or patients with advanced heart & lung disease Start with lower doses |

|---|---|---|

| Codeine | 15mg q 4hr PO + 15mg PO q1hr PRN | 7.5 mg q 6hr PO + 7.5mg PO q2hr PRN |

| Tramadol | 37.5mg PO TID PO + 37.5mg PO QID PRN | 37.5mg PO BID PO + 37.5mg PO TID PRN |

NB: Note that these are guidelines only. Doses need to be individualized to individual circumstances. The doses in some patients may need to be even lower. This may include patients with renal impairment.

| Score | Term | Description | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +4 | Combative | Overtly combative, violent, immediate danger to staff (e.g. throwing items); +/- attempting to get out of bed or chair | ||

| +3 | Very agitated | Pulls or removes lines (e.g. IV/SQ/Oxygen tubing) or catheter(s); aggressive, +/- attempting to get out of bed or chair | ||

| +2 | Agitated | Frequent non-purposeful movement, +/- attempting to get out of bed or chair | ||

| +1 | Restless | Occasional non-purposeful movement, but movements not aggressive or vigorous | ||

| 0 | Alert and calm | |||

| -1 | Drowsy | Not fully alert, but has sustained awakening (eye-opening/eye contact) to voice (10 seconds or longer) | Verbal Stimulation | |

| -2 | Light sedation | Briefly awakens with eye contact to voice (less than 10 seconds) | Verbal Stimulation | |

| -3 | Moderate sedation | Any movement (eye or body) or eye opening to voice (but no eye contact) | Verbal Stimulation | |

| -4 | Deep sedation | No response to voice , but any movement (eye or body) or eye opening to stimulation by light touch | Gentle Physical Stimulation | |

| -5 | Not rousable | No response to voice or stimulation by light touch | Gentle Physical Stimulation |

Click here to learn more about the RASS-PAL

Morphine (M) is a good opioid to start with if a strong opioid is needed. There is no strong evidence that hydromorphone (HM) is superior. Consider HM only if patient is allergic to M.

| Opioid | Usual Starting Dose | Frail Persons, very elderly and/or patients with advanced heart & lung disease Start with lower doses |

|---|---|---|

| Morphine | 5mg q 4hr PO + 5mg PO q1hr PRN | 1mg or 2.5mg q 6hr PO + 1mg PO q2hrs PRN |

| Hydromorphine | 1mg q 4hr PO + 1mg PO q1hr PRN | 0.5mg q 6hr PO + 0.5mg PO q2hr PRN |

NB: Note that these are guidelines only. Doses need to be individualized to individual circumstances. The doses in some patients may need to be even lower. This may include patients with renal impairment. Avoid morphine in patients with severe renal impairment.

In most cases, start with a short-acting opioid to facilitate titration. In rare cases, where compliance is an issue, consider a long-acting formulation plus short acting for PRNs. Do not start an opioid-naïve patient on a fentanyl patch (difficult to titrate & potency high relative to morphine). Switch to a long-acting formulation once titration completed (i.e. pain well controlled & no side effects).

Common side effects:

Constipation:

Nausea:

Somnolence:

Less common side effects:

| Drug | Approximate Equivalent Dose | |

|---|---|---|

| Oral | Subcut (or IV) | |

| Codeine | 100mg | - |

| Tramadol | 50mg | - |

| Morphine | 10mg | 5mg (3mg) |

| Hydromorphone | 2mg | 1mg (0.5mg) |

| Oxycodone | 5-7.5mg | - |

| Fentanyl | - | 50mcg |

| Methadone | About 1mg; but various according to the previous opioid dose | - |

*These are approximate equivalences and serve only as guides When switching, reduce new opioid dose by 20%-30% in all cases.

There are no clear guidelines on when to initiate an adjuvant analgesic.

Mild neuropathic pain: May use an adjuvant only.

Moderate to severe neuropathic pain: Some first titrate the opioid and then add an adjuvant if there is no good response within 5 to 7 days. Others opt to add an adjuvant to the opioid right away. 1st line adjuvants include pregabalin, gabapentin & tricyclic antidepressants.

Bone pain: NSAIDs should be used with caution in frail patients with advanced disease. Their role is limited in severe bone pain (use a corticosteroid for 5 to 7 days instead).

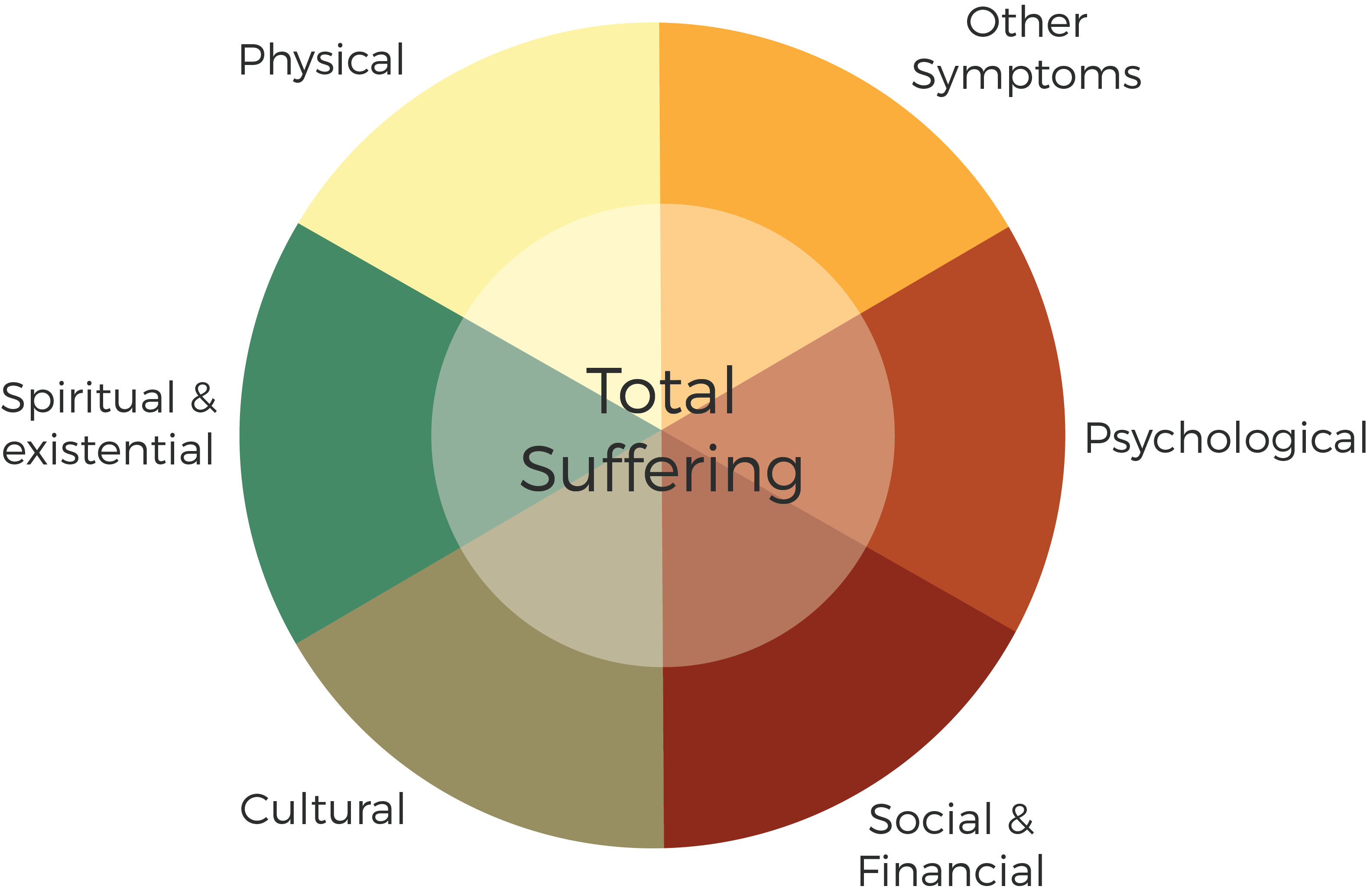

Victor Frankl, the Concentration camp survivor, wrote in his seminal book on meaning in the face of suffering (Man's search for meaning): "Man lives in three dimensions: the somatic, the mental, and the spiritual. The spiritual dimension cannot be ignored, for it is what makes us human." Suffering can occur in several of these domains, can originate in any one or more of them and often encompasses them all simultaneously. The other term that is often used is "Total Pain", a concept first proposed by the founder of modern-day hospice and palliative care, Dame Dr. Cicely Saunders. Michael Kearney in his seminal book called "Mortally Wounded" calls it "soul pain".

↓

↓

↓

The term "The Palliative Care Approach" was coined in Australia to differentiate the primary- or generalist-level palliative care from specialist palliative care. It recognizes that Palliative Care Specialists are also able to provide a Palliative Care approach but their palliative care-related skill sets and experience are more specialized.

Medical Indications

|

Patient (and family) factors and preferences

|

Quality of Life

|

Contextual features

|

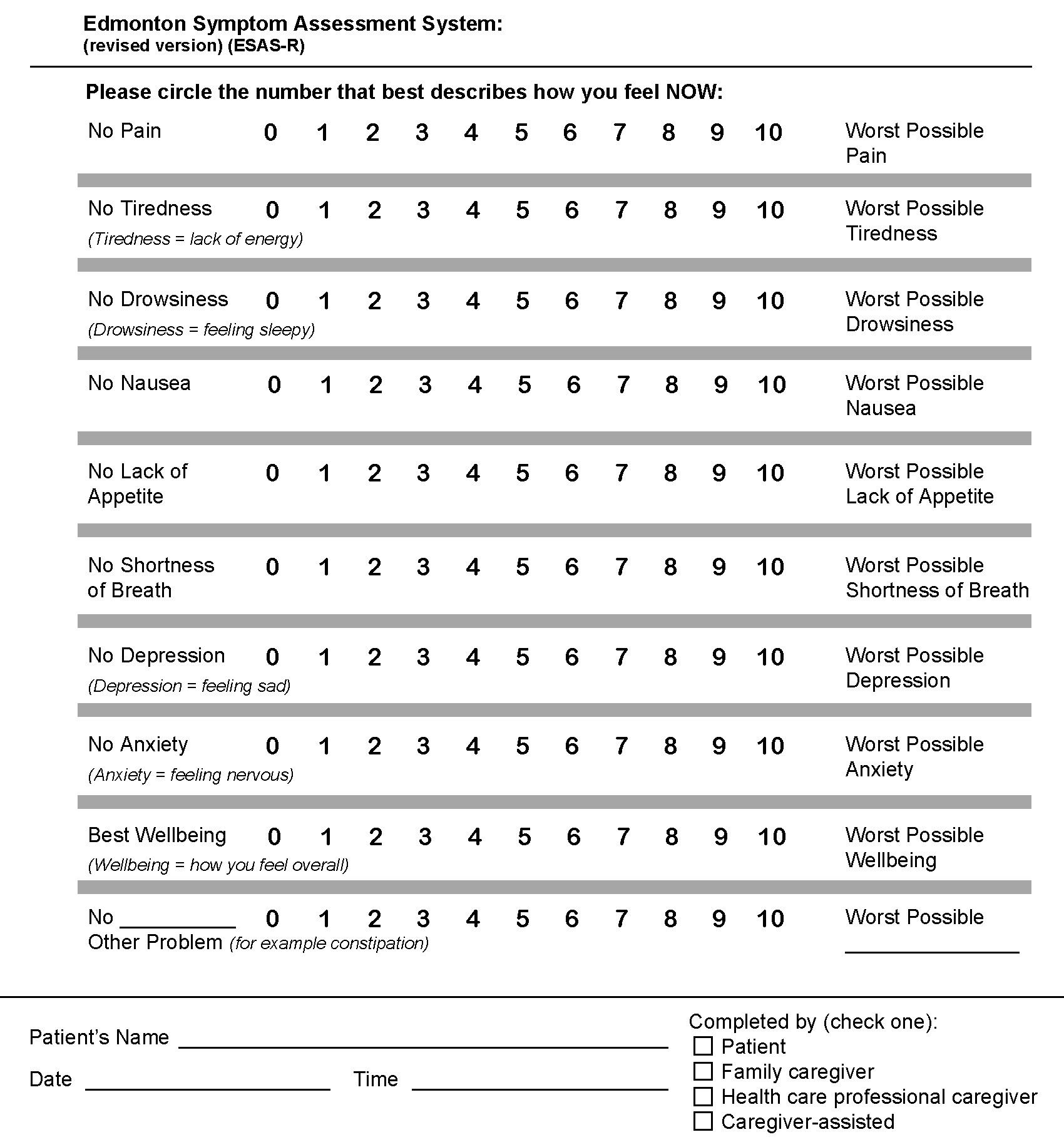

Watanabe SM, Nekolaichuk C, Beaumont C, Johnson L, Myers J, Strasser F. A multi-centre comparison of two numerical versions of the Edmonton Symptom Assessment System in palliative care patients J Pain Symptom Manage 2011; 41:456-468.

Bruera E, Kuehn N, Miller MJ, Selmser P, Macmillan K. The Edmonton Symptom Assessment System (ESAS): a simple method for the assessment of palliative care patients. J Palliat Care 1991; 7:6-9.

| % | Ambulation | Activity & Evidence of Disease | Self-Care | Intake | Level of Consciousness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 100 | Full | Normal activity No evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 90 | Full | Normal activity Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 80 | Full | Normal activity with effort Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal/Reduced | Full |

| 70 | Reduced | Unable to do normal work Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal/Reduced | Full |

| 60 | Reduced | Unable to do house work Significant disease |

Occiasional Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Confusion |

| 50 | Mainly Sit/Lie | Unable to do any work Evidence of disease |

Considerable Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Confusion |

| 40 | Mainly in bed | As Above | Mainly Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion |

| 30 | Totally Bed Bound | As Above | Total Care | Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion |

| 20 | As Above | As Above | Total Care | Minimal Sips | Full or Drowsy or Confusion |

| 10 | As Above | As Above | Total Care | Minimal/nil | Drowsy or Coma |

Visit the National Palliative Care Research Center to learn more about the PPS

Copyright © 2001 Victoria Hospice Society

| Features and descriptions\Time* | Symptom rating (0-2)** | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I. Disorientation Verbal or behavioural manifestation of not being oriented to time or place or misperceiving persons in the environment. |

|||||

| II. Inappropriate behaviour Behaviour inappropriate to place and/or for the person (e.g. attempting to get out of bed when it is contra-indicated, pulling at tubes). |

|||||

| III. Inappropriate communication Communication inappropriate to place and/or for the person (e.g. incoherence, non-communicative, unintelligible speech). |

|||||

| IV. Illusions/hallucinations Seeing or hearing things that are not there; distortions of visual objectives. |

|||||

| V. Psychomotor retardation Delayed responsiveness, few or no spontaneous actions/words; e.g. patient is difficult to arouse. |

|||||

| Total score*** | |||||

* Should ideally be completed at the end of each shift on a palliative care unit (e.g. q8 hrs)

** Scoring:

Symptoms absent = 0

Occasionally or mild = 1

Moderate to severe = 2

*** Total score of 2 or more: indicates the possibility of delirium which needs to be evaluated further with a clinical assessment.

| ECOG | % | Ambulation | Activity & Evidence of Disease | Self-Care | Intake | Level of Consciousness |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 100 | Full | Normal activity No evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 1 | 90 | Full | Normal activity Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal | Full |

| 80 | Full | Normal activity with effort Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal/Reduced | Full | |

| 2 | 70 | Reduced | Unable to do normal work Evidence of disease |

Full | Normal/Reduced | Full |

| 60 | Reduced | Unable to do house work Significant disease |

Occiasional Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Confusion | |

| 3 | 50 | Mainly Sit/Lie | Unable to do any work Evidence of disease |

Considerable Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Confusion |

| 40 | Mainly in bed | As Above | Mainly Assistance | Normal/Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | |

| 4 | 30 | Totally Bed Bound | As Above | Total Care | Reduced | Full or Drowsy or Confusion |

| 20 | As Above | As Above | Total Care | Minimal Sips | Full or Drowsy or Confusion | |

| 10 | As Above | As Above | Total Care | Minimal/nil | Drowsy or Coma |

Visit the National Palliative Care Research Center to learn more about the PPS

Visit the ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group to learn more about the ECOG

PPS: Copyright © 2001 Victoria Hospice Society

ECOG: Ma C, et al. Eur J Cancer 2010

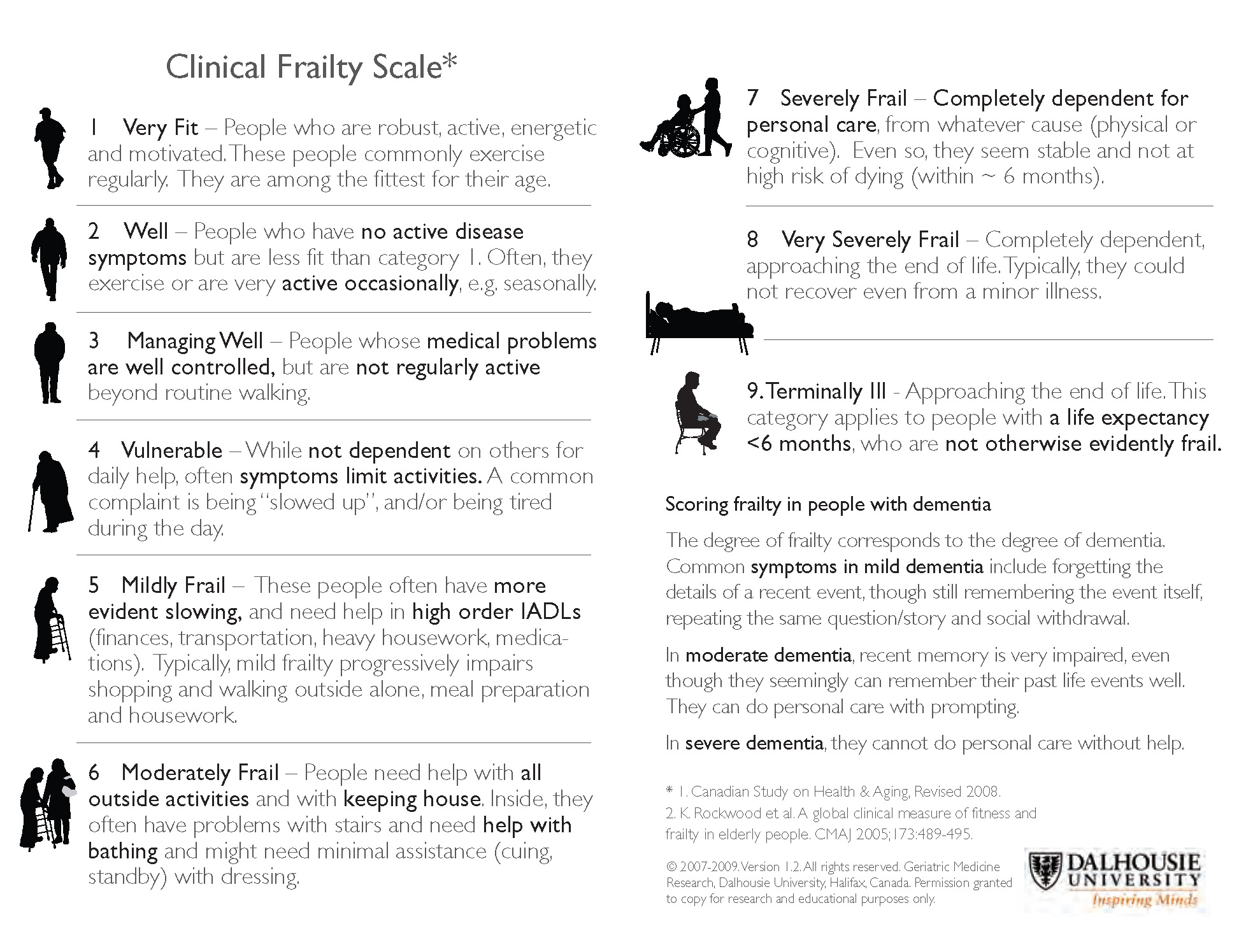

Several frameworks and tools exist to help with the challenging task of predicting prognosis. It is not an accurate science, but they provide some guidance. Functional status and albumin levels are arguably the two most important indicators. The following are three tools that may be helpful.

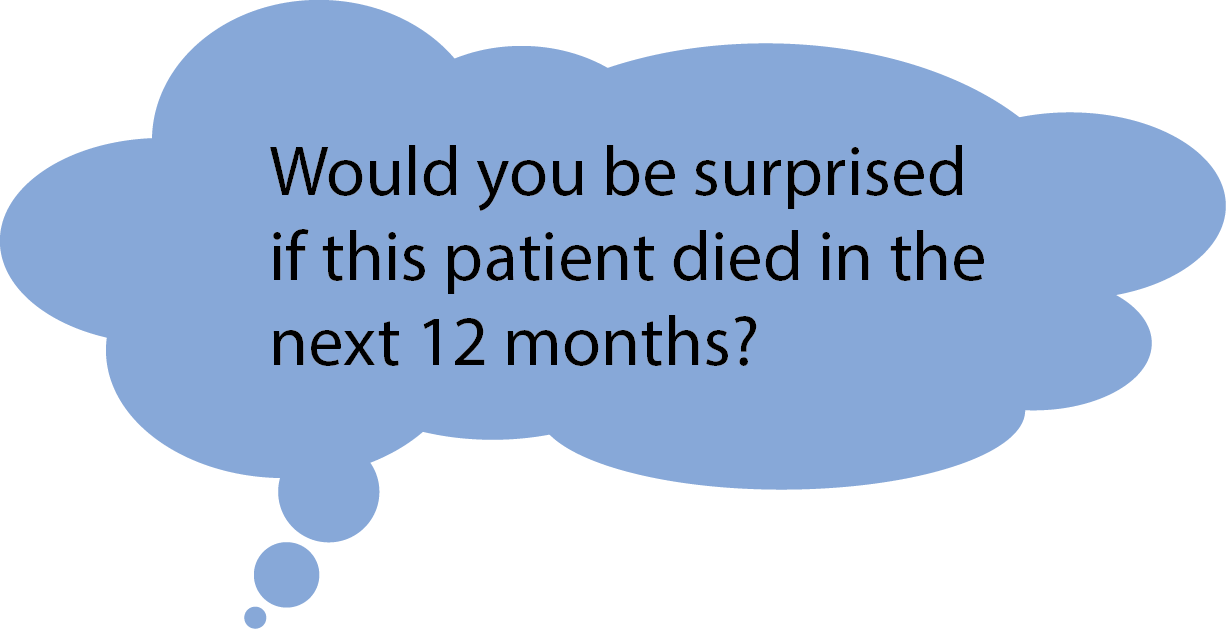

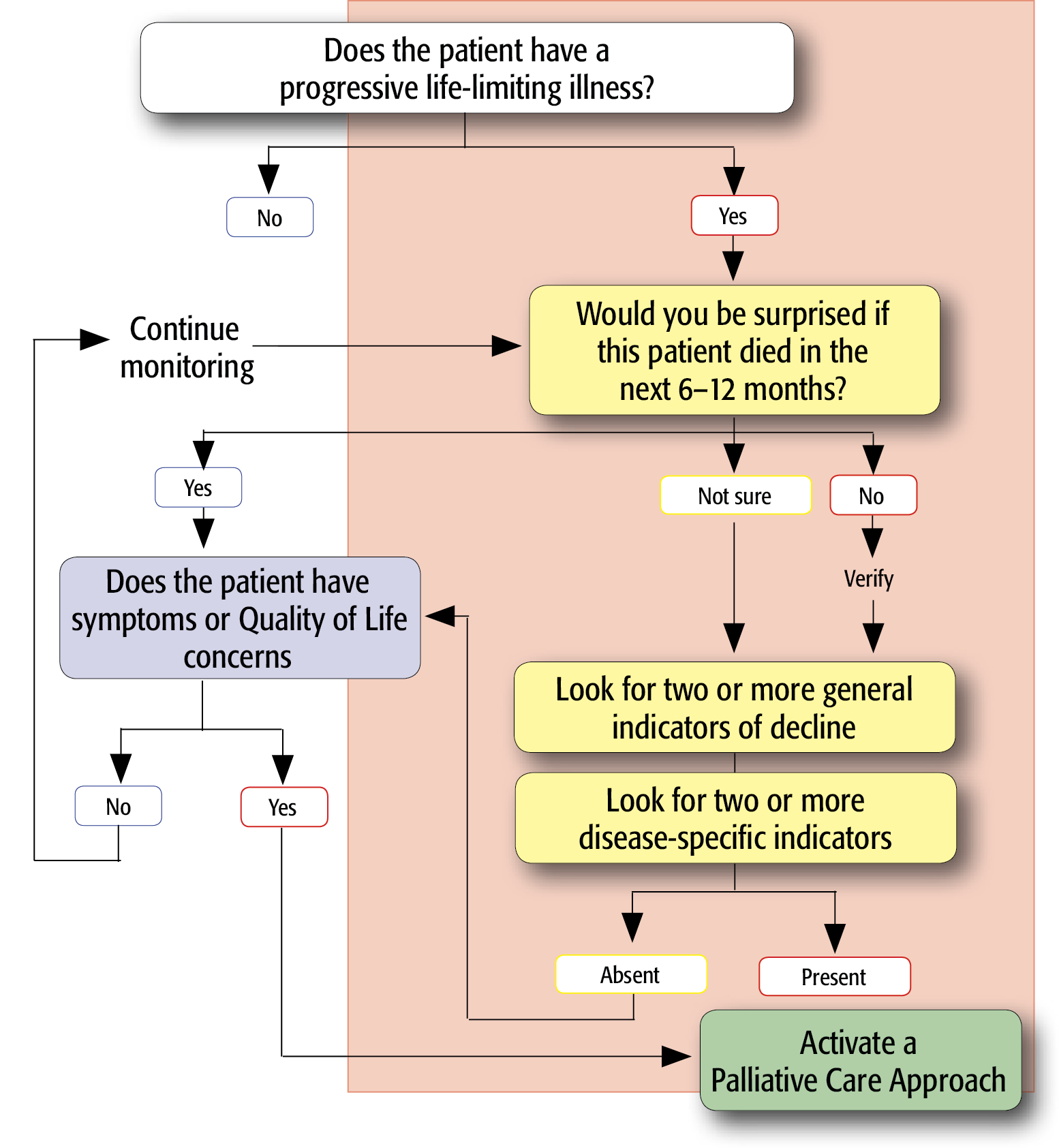

These tools (indicators), drawn from clinical experience and some evidence, correlate with an increased risk of death within the next few months. Some patients may live longer, while others may live shorter than just a few months. At the very least, they are useful in prompting a clinician to consider reviewing a patient's goals of care and activating a palliative care approach. The indicators help answer the Surprise Question (Will I be surprised if this patient dies within the next 6-12 months?).

This does not mean that palliative care is limited to the last year of life. What it does is emphasize that palliative care is not limited to the last days or weeks, or even months of life. It does not mean that we need to be absolutely certain that life expectancy is less than 12 months- this is not possible. Patients may live longer or shorter than a prediction.

The question is just to make you more vigilant in your daily practice to patients with progressive life limiting illnesses who are at a high risk of dying within the next 6 to 12 months. It allows one to activate a palliative care approach, which will still be of benefit to a patient even if he/she lives longer (e.g. symptom control, quality of life enhancement, advance care planning, etc.).

Prognostic Indicator Guidance (PIG) 4th Edition Oct 2011 © The Gold Standards Framework Centre In End of Life Care CIC, Thomas.K et al

Several frameworks and tools exist to help with the challenging task of predicting prognosis. It is not an accurate science, but they provide some guidance. Functional status and albumin levels are arguably the two most important indicators. The following are three tools that may be helpful.

These tools (indicators), drawn from clinical experience and some evidence, correlate with an increased risk of death within the next few months. Some patients may live longer, while others may live shorter than just a few months. At the very least, they are useful in prompting a clinician to consider reviewing a patient's goals of care and activating a palliative care approach. The indicators help answer the Surprise Question (Will I be surprised if this patient dies within the next 6-12 months?).

| Factor | Partial Score | |

| Palliative Performace Scale (PPS)(%) | 10-20 | 4 |

| 30-50 | 2.5 | |

| ≥60 | 0 | |

| Oral Intake | Severely Reduced (≤ mouthfuls) | 2.5 |

| Moderately reduced (> mouthfuls) | 1 | |

| Normal | 0 | |

| Edema | Present | 1 |

| Absent | 0 | |

| Dyspnea at rest | Present | 3.5 |

| Absent | 0 | |

| Delirium | Present | 4 |

| Absent | 0 | |

| Maximum possbile | 15 |

If not done already, Explore patient's understanding of illness,

discuss prognosis & goals of care.

Ensure ESAS & PPS/ECOG done at each visit.

If not done already, ensure Advance Care Planning is being undertaken.

Ensure home care resources in place (e.g. homecare nursing, primary care physician and emergency plans).

Establish plans to deal with emergencies (e.g. pain crisis).

If not done already, ensure discussion regarding code status (DNR and Advanced Directives).

Discuss preferred versus optimal place of death based on needs & circumstances.

Several frameworks and tools exist to help with the challenging task of predicting prognosis. It is not an accurate science, but they provide some guidance. Functional status and albumin levels are arguably the two most important indicators. The following are three tools that may be helpful.

These tools (indicators), drawn from clinical experience and some evidence, correlate with an increased risk of death within the next few months. Some patients may live longer, while others may live shorter than just a few months. At the very least, they are useful in prompting a clinician to consider reviewing a patient's goals of care and activating a palliative care approach. The indicators help answer the Surprise Question (Will I be surprised if this patient dies within the next 6-12 months?).

| Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Male Sex | 1 |

| Needs assistance with 1-4 ADLs at discharge | 2 |

| Needs assistance with all ADLs | 5 |

| Congestive heart failure | 2 |

| Cancer | 3 |

| Metastatic cancer | 8 |

| Creatinine >265 mol/l | 2 |

| Serum albumin 30-34 g/l | 1 |

| Serum albumin <30 g/l | 2 |

| Variable | Score |

|---|---|

| Total Score | 1-year mortality % |

| 0-1 | 4 |

| 2-3 | 19 |

| 4-6 | 34 |

| >6 | 64 |

You JJ, et al. Just ask: Discussing goals of care with patients in hospital with serious illness. CMAJ 2013. DOI:10.1503/cmaj.121274

Walter LC, Brand RJ, Counsell SR, et al. Development and validation of a prognostic index for 1-year mortality in older adults after hospitalization. JAMA 2001;285:2987-94.

Adapted from Cancer Care Ontario’s Palliative Care Disease Pathway

http://www.cpso.on.ca/policies-publications/policy/decision-making-for-the-end-of-life

| F | What is your Faith or belief? Do you consider yourself spiritual or religious? What things do you believe in that give meaning to your life? |

|---|---|

| I | Is it Important in your life? What influence does it have on how you take care of yourself? How have your beliefs influenced in your behavior during this illness? What role do your beliefs play in regaining your health? |

| C | Are you part of a spiritual or religious Community? Is this of support to you and how? Is there a person or group of people you really love or who are really important to you? |

| A | How would you like me, your healthcare provider to Address these issues in your healthcare? |

Visit the GW School of Medicine and Health Sciences to learn more about the FICA

Important notice: Please note that there are many different guidelines, published and in the grey literature, related to the management of delirium in palliative care. Unfortunately, there is a dearth of studies to guide evidence-based guidelines. The recommendations suggested in this app represent Pallium Canada's best attempts at providing useful, best practice-based suggestions. Please note that they are suggestions only and clinicians ought to apply their own assessment and decisions in all cases.

Hyperactive: Predominantly features of agitation, increased psychomotor activity.

Hypoactive: Predominantly reduced psychomotor activity. Patient appears withdrawn and often somnolent. No agitation.

Mixed: Patient oscillates between periods of hyperactivity and periods of hypoactivity

Click the boxes to learn more about managing delirium.

Look for delirium in daily practices. It is a common complication of advanced disease. Some inpatients teams use screening tools such as NuDESC.

See the criteria to confirm a diagnosis. It requires a clinical assessment by the health care professional (history and examination). Instruments specifically design to help making a diagnosis are helpful; e.g. Confusion Assessment Method (CAM).

Management requires doing three things at the same time:

| Examples of underlying precipitating causes | Examples of treatments of underlying causes |

|---|---|

| Opioid neurotoxicity | Opioid switch, dose reduction and/or hydration |

| Medications | Discontinue or reduce |

| Dehydration | IV or hypodermoclysis |

| Hypercalcemia | Bisphosphonate (or calcitonin if renal impairment) plus hydration or hydration only if mild |

| Infection | Antibiotics (therapeutic trial) |

| Brain metastases | Corticosteroid |

Click the boxes to learn more about managing dyspnea.

No results matched your search, please try again. Contact info@pallium.ca if you'd like to submit a resource.

The Pallium Palliative Pocketbook is a practical, peer-reviewed, fully-referenced resource that is intended to support safe, ethical, effective and accountable palliative clinical service. Its compact size and easily accessible information make it ideal for family/non-specialist physicians, nurses, nursing and medical students, and medical residents. It's available in a paperback and an e-book. Details on where you can get it are below.

Author: Pallium Canada

Get more information on our Website or on the Pallium Palliative Pocketbook section of the Pallium App

The Pallium Portal is a Learning Management System that organizes and tracks learner and facilitator activity. The Pallium Portal is Pallium Canada's central hub for professional development and provides access to:

If you're interested in the Pallium Portal and want to learn more about it, visit the portal by clicking the button below.

Doodles are short 1 to 3 minute-long animated videos designed to educate the general public and healthcare professionals on a topic in an engaging way. Recent Doodles have highlighted the importance of Advance Care Planning, euphemisms surrounding the word "palliative", and palliative myths. You can access all of our Doodles for free on our YouTube Channel.

Links to best-practice tools from around the world to support primary care providers in the delivery of palliative care.

Tools are organized according to the 3-step model of best practice proposed by the Gold Standards Framework (GSF): Identify, Assess, and Plan. This evidence-based approach has been adopted broadly across the United Kingdom. Work has also been done to adapt the GSF in British Columbia for an End of Life Care Module developed by the General Practice Services Committee. For resources tailored to support First Nations, Metis and Inuit families and communities, please see Tools for the Journey: Palliative Care in First Nations, Inuit and Metis Communities , a Resource Toolkit, developed by the Aboriginal Cancer Control Unit at Cancer Care Ontario

To view a detailed map of the standard of care and support that all cancer patients and their families should receive, please refer to the Psychosocial Oncology/Palliative Care Pathway (Cancer Care Ontario).

Source: CCO Website (https://www.cancercare.on.ca/toolbox/pallcaretools/)

Life and Death Matters is on a mission to develop and deliver resources to increase the capacity of the individual to provide excellent care for the dying and the bereaved.

A palliative approach can be integrated into care by all care providers in acute, emergency, long-term, and home care settings. A palliative approach does not need to be provided by specialists. The inclusion of a palliative approach across all settings means that all the dying, not just a minority of them, can benefit from the principles of hospice palliative care.

Since 2005 they have been developing and delivering palliative care education, resources and materials.From textbooks and workbooks to a complete podcast library and complimentary teaching resources, we strive to help students to learn, and instructors to teach, palliative care principles.

Source: Life and Death Matters Website (http://lifeanddeathmatters.ca/)

The Speak Up Campaign is part of a larger initiative "Advance Care Planning in Canada" and is overseen by a National Advance Care Planning Task Group comprised of individuals representing a spectrum of disciplines, including health care, law, ethics, research and national non-profit organizations.

Source: Advance Care Planning Project Overview (http://www.chpca.net/media/7437/acp_detailed_project_overview_sep_2_10.pdf)

The CHPCA Marketplace is a one-stop shop for hospice palliative care resource and information materials for health care providers, volunteers and family and informal care givers. It's an online marketplace where you can purchase palliative care resources and information materials.

Source: CHPCA Marketplace Website (http://market-marche.chpca.net/)

The Canadian Virtual Hospice provides support and personalized information about palliative and end-of-life care to patients, family members, health care providers, researchers and educators.

Source: CVH Website (http://www.virtualhospice.ca/en_US/Main+Site+Navigation/Home+Navigation/About+Us.aspx)